The Case for Embodied AI

Coming from a robotics background, the case for Embodied AI in robotics is pretty clear:

- No matter how much analysis your AI can do, it has to take actions and drive a robot.

- (Inverse) No Free Lunch: a representation is only useful in the case that it enables some downstream task. (Reverse of a representation that enables all tasks is better at none of them). I.E. Without training for action in mind, it is unlikely that a non-action-based representation will be sufficient for action.

Montezuma’s Revenge

During my undergrad and masters research, one of the largest (non-real-life) Embodied AI tasks was solving Montezuma’s Revenge.

Inspired by Claude Plays Pokemon, I came back to this game as a sort of LLM-test. I hypothesized that there were a few reasons that modern LLMs may do well (tested with OpenAI’s 4o, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and Claude Sonnet 3.5. Not more advanced models due to lack of funding).

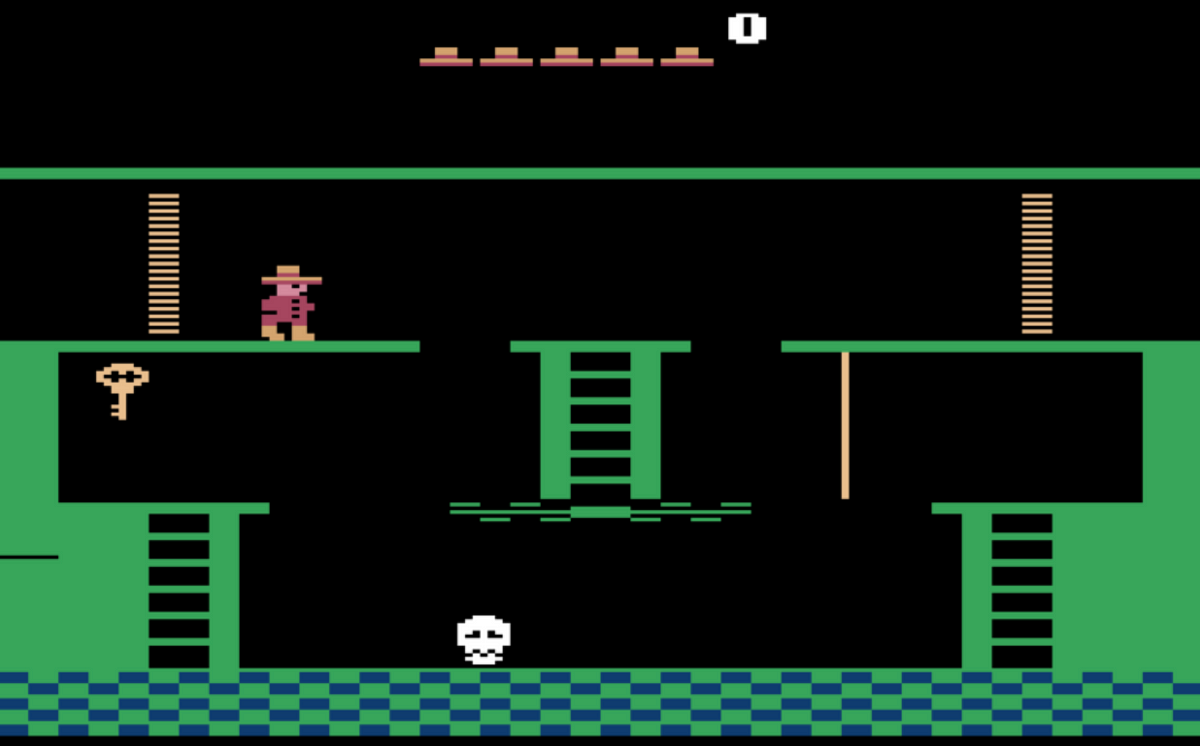

- Montezuma’s Revenge relies on general real-world context. For example, keys should be collected and open doors, skulls are bad, you should go up or down ladders, etc. Due to their large corpus of background and common-sense knowledge, LLMs should have this context.

- Even though they aren’t planning algorithms in the true sense of the word, LLMs are very good at putting together and acting on laid out plans (see chain of thought, TODO list tools, Claude Code)

- With the addition of vision inputs, VLMs (Vision Language Models) should be able to make semantic sense of the world around them. This should be able to achieve the dream of playing games (and acting in the real world) based on pure visions (though as far as I am aware, Claude Plays Pokemon does not do this).

Starting with a mini-experiment - playing cartpole - I initially found quite negative results, and the LLMs were unable to even identify the angle of the cart properly and performed approximately at random chance. After some prompt tuning to get the visual image understanding correct, it did much better, regularly achieving 100+ reward per episode.

I then moved to Montezuma’s Revenge.

I was initially quite hopeful, with the agent picking actions like down and climbing down the initial ladder, with reasoning such as I must reach the bottom or I must reach the key. However, as the floor right under the ladder is an escalator (it pushes the character to the side), the agent initially fell off the platform to its death.

I tried a few methods to get around this, such as explaining what and how to identify escalators, explaining fall damage, and even giving hardcoded instructions to the agent telling it to jump to the platform on the left. But I was unable to get it to progress further.

I suspect with even more prompting (or perhaps even a RAG-system with relevant video game or Montezuma’s Revenge experiences/actions), it may be possible to get around this. But I had significantly hoped that it would not require so much architecture - that the VLM itself had enough experience via pre-training and enough ability to adapt based on test-time reasoning. This likely indicates (at least) one of three things:

- The model itself does not have enough visual or language based experience with video games

- The model’s sense of intuitive physics or other embodied qualities is incomplete.

- The visual perception system is not yet sufficient to do high-level reasoning.

Computer Use Agent (Tax-Specific Software)

As part of my job at Pillar Advisors, I was working on automating tax-specific workflows (ex: calculating tax savings for 401k/IRA contributions and their business equivalents) that change on a regular basis and are not well documented online. Furthermore, the software that encodes these looks like it was originally written in 2009 (i.e. doesn’t follow modern day UI design patterns) and only runs on a windows computer.

We initially thought this would be easily automatable via a sandboxed computer-use agent. Computer use agents seem to be getting more popular (ex: (OpenAI Operator)[https://openai.com/index/introducing-operator/], (Amazon Nova)[https://nova.amazon.com/act]) though they tend to all be focused on browser use agents. We had success automating browser workflows via the Playwright MCP.

Of course, this would be a true computer use agent, moving a mouse and typing via a keyboard. At first, the agent properly identified a plan of action based on the screenshot that was correct, and began executing. However, despite our best attempts, the agent regularly missed the buttons it intended to click. We tried:

- Prompting the agent to confirm the mouse is in the right place before clicking.

- Automatically edit the image to have a very large red circle around the mouse.

- Prompting the agent to ensure that it clicks the button and the expected action happens before moving to the next step.

- Automatically editing the image to have grid lines with px coordinate numbers.

- Telling the agent to find grid coordinates before clicking.

However, the agent still continued to miss the button when clicking.

Of course, we could go the browser-agent approach and make tools that click on specific buttons (ignoring the technical difficulties here - web agents have it easy because they have access to the HTML DOM). However, this points to a larger embodiment issue with our current agents: our agents can identify what to do but not actually act upon it. This has similarities to Moravec’s paradox - that reasoning is relatively straightforward but sensing and perceiving the world is quite difficult.

There are a few potential reasons for this case:

- The VLMs used in this experiment (OpenAI 4o, Openai o3, Claude Sonnet 4, Gemini 2.5 Pro) are not action-models and thus don’t encode the notion of acting on a computer

- The computer use tools themselves are difficult to use (though this doesn’t explain the lack of ability to properly tell if the mouse is over a button).

- The image embeddings are not sufficiently suited toward fine-detail action (ex: pixel coordinates of a mouse pointer) rather than high-level descriptions (ex: “What is in this image?”). This is yet another case of the No Free Lunch Theorem.

This also explains why frontier labs are training computer-use-specific models. In other words - embodied models that act within their environment, which in this case happens to be a computer or web browser.

Conclusions and Future Steps

Based on both of these experiments, I believe that Embodied AI (that knows about and can act reasonably in its environment) is heavily based on the training schemes of the base models. Whether this is done by reinforcement learning, fine tuning, or some other method is perhaps an open research question. However, it seems quite clear that the (information-theoretic) overlap between the training tasks of the visual-language models (ex: describe this scene vs look at the location of my mouse pointer) can cause significant (lack of) downstream performance capabilities.

Some food for thought: A human that has never used a computer before also would have a lot of difficulty navigating tax software (as a proxy example, my grandparents must be taught to use new software). As we go through life, we specialize in specific domains and learn specific skills, yet we expect a single Visual-Language model to be able to solve a wide variety of problems.

In the short to mid term, I believe that training embodied, action-based agents (ex: see reinforcement learning from coding challenges and how it enabled to rise of coding agents) will allow us to achieve human-level (or even (superhuman level)[/blog/nature-of-superintelligence-pantheon/]) performance on specific domains or tasks.

In order to achieve broad-level human/superhuman level performance across all tasks, I suspect that some sort of (either implicitly or explicitly learned) hierarchical architecture will get us around the No Free Lunch Theorem. If an agent could detect and “load in” the relevant module (ex: A computer navigation module), this would skirt the representational and test/train overlap issues.